The editors met guest author Jen Cardenas at the 2021 Popular Culture Association annual conference, where we caught their engrossing presentation on the metamodern qualities in this film. We’re delighted that they introduced us to the film and agreed to write a condensed version for What is Metamodern? Jen is a graduate student in the Media Studies program at the University of North Texas with a bachelor’s degree in English, popular culture, and film from Texas State University.

My favorite film of 2019—nay, my favorite superhero film of all time, is Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse. The protagonist is Miles Morales (voiced here by Shameik Moore), the newest incarnation of Spider-Man and the first Afro-Latino superhero on the big screen; when I watched it, it was the first time I felt like a superhero film saw me. This award-winning 3-D animated film is about alternate-version Spider-heroes coming to Miles’ universe after he’s bitten by a radioactive spider. Then he’s pulled into a conflict between the villain, Kingpin, and the many spider-heroes. By the end of the film, Miles finds a meaningful identity as Spider-Man, despite such a thing seeming impossible to him at the start. Spider-Verse is a coming-of-age story that affirms individuality and purpose, but it’s also a deeply intertextual and self-aware pastiche, thus seeming to oscillate between modernism and postmodernism—but is it truly metamodern? In this article, I’ll use a favorite method of mine to explore whether a given text has metamodern characteristics – one that modifies and adds to Timotheus Vermeulen and Robin van den Akker’s familiar model. I employ Simon Radchenko’s set of five criteria as seen in his analysis of video game The Last of Us (2013): oscillation, coherency, interconnection, reconstruction, and emotionality.

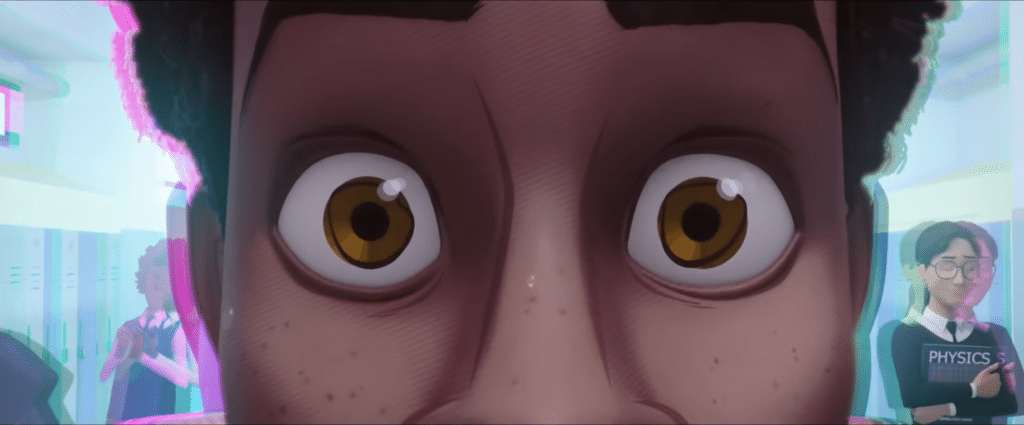

The tone of Spider-Verse oscillates between postmodern ironic and modern heroic moments. The film is, self-consciously, the latest in a recent barrage of Spider-Man movies: it opens by acknowledging the “already said” (in the words of Umberto Eco) with the line “Alright, let’s do this one more time.” This remark is followed by the image of a comic book on a black surface outside of the film’s diegesis, beginning a metatextual motif that repeats every time a new Spider-hero is introduced. The “original” Spider-Man introduces himself directly to the audience by making several intertextual jokes about past Spider-Man films. This self-aware opening is followed by the more conventional introduction of the film’s protagonist, Miles, an upbeat character who nonetheless struggles with the kind of apathy and cynicism characteristic of postmodern malaise. When assigned a book report on Great Expectations, which must include a discussion of who he wants to become, Miles creates a cynical art piece reading “no expectations.” There’s a barrage of other postmodern, genre-savvy gestures as the movie goes on—always reminding the audience of the construction they are watching. However, these ironic moments are interspersed with all the conventional milestones of the hero’s journey that puts Miles on a path toward eventual self-realization, like any individualist tale one finds in modern or pre-modern literature.

For example, in a dark moment Miles asks his jaded mentor, “When will I know I’m ready [to be Spider-Man]?” and Peter B. Parker (played by Jake Johnson, an actor with many arguably metamodern works in his filmography) replies, “You won’t. It’s a leap of faith.” This line inspires Miles to make his big leap of faith in the “What’s Up, Danger” scene. At the end of that sequence, Miles’ comic drops into the metatextual space with a triumphant note in the score, using an ironic motif for a sincere moment. For the finale, Miles meets back up with the other Spiders and sends everyone back to their respective dimensions. Before he goes, Peter B. Parker asks Miles, “How do I know I won’t mess [my life] up again?” to which Miles replies, “You won’t.” Peter, realizing his meaning, repeats back his own words from earlier: “Right. It’s a leap of faith.” To put this into Vermeulen and van den Akker’s metamodern terms, the characters “[move] for the sake of moving” toward an “impossible possibility” (“Notes”) with a “hope […] that needs to be learned, a rare good that needs to be fought for” (“Utopia”). By the end of the film, both mentor and mentee gamble everything on the slim possibility of a better future, having learned how to hope for something good despite their many failures and grim circumstances.

Spider-Verse’s core premise is contact between characters from alternate timelines that form relationships, with a coherence that Radchenko considers characteristic of metamodernism. The main cast of the film seem irreconcilable at first—a sort of postmodern chaos. The Spider-heroes come from alternate universes within the film’s diegesis and are sometimes drawn and animated in different styles to reflect these differences; each Spider is based on real-life comics depicting alternate universe spider-heroes. More than that, these other Spiders’ very molecules reject being in Miles’ universe and will die if they remain. However, this obstacle is not insurmountable; a repeated moment throughout the film is the Spider-heroes saying to each other upon meeting, “You’re like me.” The Spiders forge interconnections with each other that result in lasting growth, even if they cannot remain together for long: they deal with grief, mature into parenthood, or find identity. The Spider-heroes are in a fragmented world, yet they can make sense of it and see a part of themselves in Spider-heroes from other universes.

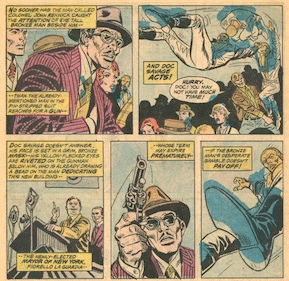

Spider-Verse reconstructs the superhero genre to make room for people of color by reappropriating old visual styles—breaking them down and building them into something new. The film doesn’t copypaste an Afro-Latino teenager into a superhero role; it reshapes the genre around him. When oppressed minorities—postmodern “subjects-in-crisis”—reappropriate nostalgic aesthetics (usually those from the modern period) to make space for themselves, they create a metamodern text, as observed in James Brunton’s study of Black women’s poetry. Further, the film’s striking visual design deliberately evokes a specific period of comic book history—the Silver Age (circa 1956–1970)—during which the first Spider-Man comic appeared in 1962. The Ben-Day Dots, hard facial lines, and misaligned color palettes that are simulated in Spider-Verse’s animation style were characteristic of Silver Age comics due to the technological limitations of screen printing as noted by comic book scholar Sam Summers. However, these visual elements were phased out by the time Miles first appeared in Marvel comics in 2011, since digital printing has been the norm in the industry since the 90s. Despite this, Spider-Verse depicts Miles in the nostalgic aesthetics of that bygone Silver Age period—a past in which he would have been more unwelcome due to his race. Therefore, the film’s aesthetics reconstruct the past to make room for Miles and for all people of color in the world of superheroes.

The film’s crowning reconstructive jewel is the “What’s Up, Danger” sequence, in which Miles creates his own superhero costume by literally painting over the dead Spider-Man’s suit, recreating it for his own use. By using the “aesthetic toolbox of the past,” in Brunton’s words, associated with a bygone era of comic books and allowing a protagonist of color to literally paint over those aesthetics, Spider-Verse reconstructs the superhero genre for people of color.

In addition to the visuals, the film’s sound also reconstructs the superhero genre for Miles’s journey in accordance with what media and race scholar Kristen Warner calls “sonic visibility”: “a tool that enables audiences the opportunity to not only feel represented by onscreen characters who look like them but also hear their culturally specific tastes, histories, and nostalgia through the soundscape” (231). Superhero movies, especially Marvel movies, tend to feature orchestral scores that resemble generic “temp music” (the stand-in music used in early film edits that is often borrowed from similar past films). Miles, on the other hand, is introduced with a diegetic hip-hop track that he sings along with, linking his character development and personal identity to the genre. The “What’s Up Danger” sequence features a hip-hop track of the same name, which is subtly underlaid by two orchestral leitmotifs used earlier in the film. Since orchestral scores play a backseat role in the scene that delineates Miles’ identity in favor of hip-hop music, Spider-Verse places Miles in a space that reconstructs those mainstream signifiers for a story about a person of color in more than just visuals, but also in sound.

Finally, emotion and sincerity are a driving force in the story. The final tipping point before the “What’s Up, Danger” sequence is a moment where Miles’ father affirms his individuality: “I see this… this spark in you. It’s amazing, it’s why I push you. But it’s yours, and whatever you choose to do with it, you’ll be great.” This audio plays again at the beginning of the aforementioned sequence, giving Miles the confidence to begin his apotheosis. Demonstrably, though Miles needs connections with his fragments to be whole, he also needs emotional support from his roots in order to grow. Miles discovers the “pragmatic idealism” that V and V have suggested characterizes metamodernism, placing earnest value on things such as family, individuality, friendship, and the greater good in spite of the chaotic story world he occupies.

The elements of the visuals, dialogue, and soundscape of Spider-Verse I’ve discussed here make for a quintessentially metamodern movie. Despite the film’s intertextuality, excess, and irony, it still gives the audience all the milestones of the hero’s journey towards self-discovery wherein the key is interconnection between vastly different realities; thus, the film’s oscillation between postmodern and modern sensibilities creates a coherent, emotional, relationship-focused, and reconstructed text. In the world of Spider-Verse, companionship, heroism, morality, and authentic identity are still worth seeking out even in a universe where one’s image is reflected back at oneself in endless funhouse mirrors. On top of all that, the film doesn’t just put people color in a superhero story—it takes the genre apart and rebuilds it around people of color.

There’s one final moment near the end of the film that could be chosen to demonstrate Spider-Verse’s metamodernity. During the film’s climax, when the interdimensional portal that brought the other Spiders to his universe is about to collapse, Miles finally gets a good look at the multiverse that was glimpsed earlier in the film. What he sees is a universe fragmented, but one whose fragments are connected by endless web strands. To me, this evokes the words of Michel Houellebecq, as quoted by early metamodern theorist Alexandra Dumitrescu: “a magnificent interweaving, vast and reciprocal.”

Works Cited

Brunton, James. “Whose (Meta)Modernism?: Metamodernism, Race, and the Politics of Failure.” Journal of Modern Literature, vol. 41, no. 3, Indiana University Press, 2018, p. 60–76. EBSCOhost, doi:10.2979/jmodelite.41.3.05.

Dumitrescu, Alexandra. “Interconnections in Blakean and Metamodern Space.” Double Dialogues, 2007, https://web.archive.org/web/20120323035251/http://www.doubledialogues.com/archive/issue_seven/dumistrescu.html.

Eco, Umberto. Postscript to The Name of the Rose. First Mariner Books, 2014.

Every Frame a Painting. The Marvel Symphonic Universe. 12 Sept. 2016. YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7vfqkvwW2fs.

Jameson, Frederick. “Postmodernism and Consumer Society.” Critical Visions in Film Theory, edited by Timothy Corrigan et al., Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2011, pp. 1033–1041.

Persichetti, Bob. Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse. Sony, 2018.

Radchenko, Simon. “Metamodern Gaming: Literary Analysis of The Last of Us.” Interlitteraria, vol. 25, no. 1, University of Tartu Press, June 2020, pp. 246–259. EBSCOhost, doi:10.12697/IL.2020.25.1.20.

Sideways. The Sound of the Spider-Verse. 31 March 2019. YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ozbKHKntpCc.

Summers, Sam. “Adapting a Retro Comic Aesthetic with Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse.” Adaptation, vol. 12, no. 2, Oxford University Press / USA, Aug. 2019, pp. 190–94. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1093/adaptation/apz014.

Vermuelen, Timotheus, and Robin van den Akker. “Notes on Metamodernism.” Journal of Aesthetics & Culture, vol. 2, no. 1, Routledge, Jan. 2010, pp. 5677–5691. doi:10.3402/jac.v2i0.5677.

Vermeulen, Timotheus, and Robin van den Akker. “Utopia, Sort of: A Case Study in Metamodernism.” Studia Neophilologica, vol. 87, Jan. 2015, pp. 55–67.

Warner, Kristen J. “The Pleasure Principle of Magic Mike XXL: Sonic Visibility Toward Female Audiences.” COMMUNICATION CULTURE & CRITIQUE, vol. 12, no. 2, 16 July 2019, pp. 230–46. EBSCOHost, doi:10.1093/ccc/tcz018.