With this guest-authored piece, WiM makes our first foray into into the topic of metamodern video games! We met author Meredith Pasahow at the 2021 Popular Culture Association annual conference, where a casual conversation led to the idea of this piece. Meredith is a PhD candidate in the English, Speech and Foreign Languages Department at Texas Women’s University.

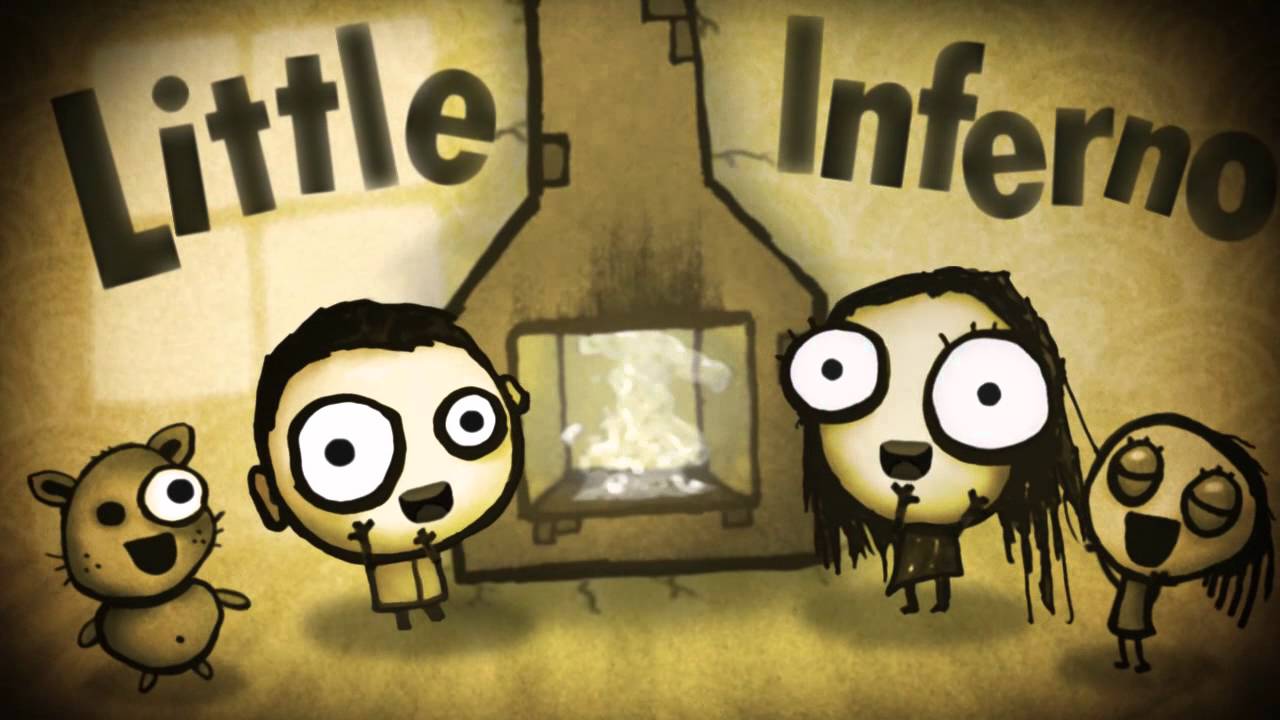

Little Inferno: An Indie Game Full of Metamodern Surprises

Little Inferno is a puzzle-solving video game, released in 2012 by the Tomorrow Corporation. It is a first person, single player game wherein the player has a simple goal: buy objects from the in-game catalog, and survive the cold by burning them in your Little Inferno Entertainment Fireplace. I first came across Little Inferno in 2016, before I had discovered the notion of metamodernism. Now, five years later, having learned of the theorization of this new cultural sensibility, I thought back to Little Inferno and how it makes an excellent example of a metamodern video game.

The mechanics (that is to say, the functional aspects) of the game are simple: to burn an object, click and drag it into the fireplace, then click on it to light it on fire. Burning objects gives you in-game money that you can use to buy more objects. To buy an object, open your catalog and click on the picture of it to purchase it, then wait for it to be delivered to you. If you solve a puzzle by burning the right set of objects together, you get both extra money and stamps. The stamps can be used to decrease delivery time and get your objects to you faster. There is no mechanic to look left or right; you are situated in front of the fireplace, and that is all you can look at for the majority of the game.

At first, Little Inferno seems to be a postmodern dystopian response to and critique of the follies of capitalism, but in actuality, it is a deeply emotional journey of self-realization conveyed via this critique, and one that also supplies the hopeful notion that there is a world beyond both neo-liberal capitalism and the problematics of relying on postmodern critiques – all of which is rather metamodern. Set sometime in the future, or perhaps an alternate present, the world of Little Inferno has been covered in snow for “as long as anyone can remember.” But not to worry, because the Tomorrow Corporation is here, with their Little Inferno Entertainment Fireplace!

The commercial for the product, which serves as both a game trailer and an in-game learn-the-mechanics device, encourages kids to “Just sit by the fire, burn all your toys, and stay warm.” Because of the commercial, the player assumes – rightly so, as it turns out – that the main character of the game is also a child. The nihilistic cynicism of encouraging children to burn their toys for survival, the layers of self-referencing realities – all of that is postmodern. But once you get deeper into the game, the metamodern sensibilities of the narrative are really revealed.

In addition to buying things from the Tomorrow Corporation catalog to burn in order to earn money, then use that money, buy more things, burn them, repeat, there is also a list of puzzles to solve, should you, the gamer, choose to do so. You also receive letters from a few different characters over the course of the game: The Weather Man informs you that it is still snowing; the head of Tomorrow Corporation, Miss Nancy, tells you how to properly use your fireplace.

The Little Inferno Entertainment Fireplace is, “not like other games,” explains Miss Nancy. “There are no points. There is no score. You are not being timed. Just make a nice fire… and stay warm in the glow of your high definition entertainment product!” And the same is true for the game itself; there is no way to lose the game. You can spend all your money, but when you burn the things you’ve bought, the game automatically gives you more money. You can let your fire go out, but there is no freezing mechanic, so you can sit in front of your dead fireplace indefinitely and the game will not freeze you to death or otherwise force you into a game over. There is no game over. There is only moving forward.

In addition to the meta-cute (to use Greg Dember’s coinage from his article “Eleven Metamodern Methods in the Arts”) found throughout the game – between Miss Nancy’s enthusiastic reactions to your minor successes and the idea of children burning their toys to keep their family warm – there are three other metamodern sensibilities prominent in Little Inferno. The first is that of the tiny. Metamodern cultural products use the tiny, according to Dember, “… in order to create vulnerability and intimacy, bringing the reader of a work closer to the felt experience expressed in the work.” Little Inferno does this by creating a very small world within which the gamer interacts.

The gamer sits in front of their fireplace, unable to turn left or right, or to move away from the fireplace for the majority of the game. This forces the gamer into focusing on the gameplay and on the limited world that has been created by the game developers. The gamer is able to focus more closely on the perceived warmth of the fire, and the way the objects feel and have weight when you pick them up. Because of the extreme close-up focus that the game gives, the gamer is able to become more immersed in the world offered.

The second metamodern element that comes into play in Little Inferno is the idea of the narrative double-frame. In this game, the narrative outer frame built by the developers is the snow covered world that forces the protagonist, and everyone else, inside and in front of their fireplaces. But as the story progresses, the protagonist starts receiving letters from a neighbor, Sugar Plumps. These letters are the attempt of Sugar Plumps to connect with the protagonist, and therefore the gamer. Through these letters, we, the gamers, are able to form an emotional connection with Sugar, sending different objects back and forth and slowly learning more about Sugar as a person. Thus begins the inner frame, one that focuses on the emotional arc of the protagonist.

Because this is the only outside connection we have beyond our fireplace, we have no choice but to become attached to Sugar as a character and as our friend. Although her letters begin by being signed with a simple, “From, Sugar Plumps,” she gradually starts signing her letters “Your Friend” or “Love”. This signals that we are meant to feel as if growing closer to Sugar, and forming a deeper emotional bond with her.

She encourages us (both protagonist and gamer) to try to look beyond the fireplace, and explore the world around us. In that sense, the walls of the inner frame push against the outer frame, putting the emotional narrative at the forefront and pushing us to expand what we know of our world. And so, when Sugar Plumps disappears, it is likely to cause a feeling of emotional devastation for the gamer. We are very suddenly alone again, without this intimate relationship we’ve built with our neighbor. There is a sharp oscillation between companionship and solitude, happiness and fear. This abrupt exit only underlines the deep and sentimental bond developing between the protagonist (and therefore the gamer) and Sugar.

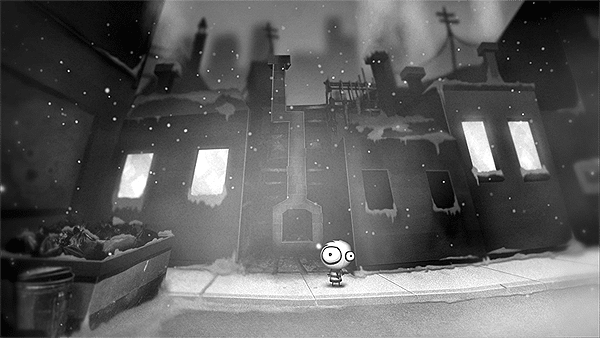

The final metamodern sensibility is the concept of hyper self-reflexivity. Because the metamodern version of self-reflexivity focuses on felt experience, according to Ceriello and Dember, once again, we have a focus on the emotional narrative, both of the protagonist and of the consumer of the media in question. Little Inferno does this by bringing back Sugar Plumps after her disappearance. She had managed to leave the narrative framing of the fireplace and has gone to explore the world. She had even found a place without snow. She writes to the protagonist, and therefore the gamer, that we must escape the confines of our fireplace and see what else the world has to offer. We oscillate between fear and solitude to joy and companionship. And so, at Sugar’s behest, we (gamer and protagonist) burn down our house in order to see the outside world.

The game shifts then from first person to third person, and we see ourselves for the first time. Once our house is burnt down, we are able to explore the world more freely, though still in a limited fashion. This massive change in both point-of-view and game-play mechanics begs for a deeper exploration than the confines of this article can provide. Are the game developers telling us that only once we are free of all our possessions do we truly find ourselves? Are we only able to discover our true selves by communicating with the outside world? Must we, the audience, burn down our metaphorical houses in order to go on a journey of self discovery? I leave these questions for you to ponder. But not only must we move forward, as the game so wisely tells us time and time again, we can only go forward.

We meet the mailman, who has been with us the entire time but we have never noticed before, since we were so focused on our fireplace. When the mailman greets us, one of the options for a reply is, “I just found out I exist…” This fits with what Ceriello and Dember have written of hyper self-reflexivity, which is that, “This self-awareness or witnessing mentality is kind of like a breaking of the 4th wall.” In our sudden, startling awareness of our own existence, we as the protagonist are performing acts of both fourth-wall breaking and becoming more deeply self-aware.

We, both as player and protagonist, are also made aware not only of our own existence, but of the existence of others around us. Now that we (the players) can look around more, we can take a step back from the game and observe it as ourselves, rather than being so completely immersed in the world of the fireplace. When we were focused on our fireplace, the mailman came and went without notice. Miss Nancy and the Weather Man both wrote letters to the protagonist, but their contact remained remote. Now, outside of those confines, we are able to see these others as full and complete people, who exist beyond just the letters they wrote.

While the concept of the game and its surface message critiquing capitalism (i.e.: buy things and burn them, though it won’t bring you satisfaction, merely survival) may seem to be postmodern, the further the audience explores the Little Inferno game, the more they are able to see the metamodern sensibilities in play. The game travels beyond the postmodern into a new “there”, despite postmodernism insisting that there is no “there” to get to. But the game does go “there”, and that “there” is settled firmly in the metamodern.