La La Land, the recently released film starring Emma Stone and Ryan Gosling, and directed by Damien Chazelle, does not submit complacently to categorization, but we feel it can be at least partly labelled “metamodern.”

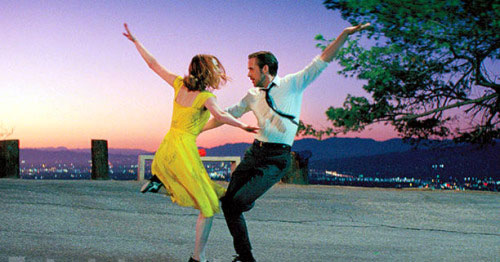

The story in a nutshell: Ryan Gosling as Sebastian is a struggling, stubbornly purist, jazz pianist, while Emma Stone portrays Mia, an aspiring actor and playwright with a day job in a coffee shop at the Warner Brothers production lot. Their first encounter is in their separate cars in an L.A. traffic jam, and after that, they keep running into each other, at first getting on each others’ nerves, but eventually finding chemistry. The film follows their attempt to negotiate a relationship while each pursues creative ambitions. Oh, and, one more thing: It’s a musical with full-on, choreographed production numbers!

As Owen Gleiberman writes, for Variety, “Chazelle wants to make a musical that celebrates the classic Hollywood vision of love as spiritual perfection. But he also wants to make an age-of-alienation love story that undercuts the old simplicities. He has the right to do both.” Put in the language of epistemic analysis, one might restate Gleiberman’s observation thusly: Chazelle has made a film that exemplifies metamodernism by oscillating between unabashed, modernist extravaganza and postmodern self-deflation. The boy doesn’t get the girl in the end, and the girl doesn’t get the boy, but yet… they sort of do. (Since this is a recently released film, we are being more coy than usual, to avoid spoilers.) The Hollywood ideal of artistic triumph is first shown as hollow fantasy, then shown to be attainable through grit and determination, and then shown to come at a cost.

La La Land is hyper-reflexive too: It’s a film about people in the film business and it’s a musical about people in the music business. Musical production numbers that are both stunningly fantastic (modern) and subtly self-winking at their contrived nature (postmodern), create an outer narrative frame that embeds authentic piano performances by Sebastian/Gosling that become all the more poignant when one understands that Ryan Gosling played them himself for real, and that he’d had very little experience playing piano before he began training for the film by practicing three hours a day, six days a week, for three months. His playing is both technically impressive and emotionally compelling, a beautiful sharing of his own inner world. This is the real guy doing the real thing: it’s not a skilled expert, pinch-hitter “body double” presenting an illusion.

Similarly, when we see Mia/Stone performing in auditions, we are aware of her in two ways. We see the character, Mia, in the familiar position of an actor anxiously trying to impress cold-faced casting directors. And we simultaneously get a glimpse of the real Emma Stone doing her real actor thing — taking words from a page and imbuing them with her own intensified humanity, like in her/Mia’s first audition when she freaking kills it, but still doesn’t land the part. Given these levels of reflexivity, there is a heightened sense that we are seeing through the character to Emma Stone herself. These moments (both Gosling’s and Stone’s), along with La La Land’s bivalent attitude towards musical theatricality, provide the metamodern heart of the film.

*****

For more on metamodernism in Hollywood and/or Ryan Gosling, check out our earlier post: